Week 5 Learning Journal

LPIC-1: System Administrator Exam 101 (v5 Objectives)

- Definition of Pseudo File System:

- Pseudo file systems are created by the Linux kernel in RAM during system boot-up and exist only while the system is running.

- Everything is a File in Linux:

- All components in Linux, including files, folders, hardware devices, processes, and commands, are treated as files.

- /proc Directory:

- Contains information about processes currently running on the system, including CPU info, memory info, system partitions, and uptime.

- /sys Directory:

- Provides information about hardware connected to the computer and the Linux kernel itself, accessible as plain text files.

- Using Basic Commands:

- Basic commands like

ls,cat, andcdare used to navigate and read information from pseudo file systems.

- Basic commands like

- Understanding System Initialization:

/procdirectory contains details about the system’s initialization process, including the init process and its command line details.

- Simplified Information Access:

- Pseudo file systems simplify accessing and understanding system information, aiding in system administration tasks and troubleshooting.

- Linux Kernel Overview:

- The Linux kernel serves as the core framework of the operating system, facilitating interaction with hardware components and managing system resources.

- Monolithic Kernel Architecture:

- Linux follows a monolithic kernel architecture where the kernel handles all memory management and hardware device interactions independently.

- Dynamic Kernel Modules:

- Additional functionality can be dynamically loaded and unloaded through kernel modules, allowing for seamless integration of new drivers and features without the need for a system reboot.

- System Information Retrieval:

- Basic information about the currently running kernel can be obtained using commands like

uname, which provides details such as kernel version, architecture, and more.

- Basic information about the currently running kernel can be obtained using commands like

- Managing Kernel Modules:

- Kernel modules currently loaded can be listed using

lsmod, and detailed information about a specific module can be retrieved usingmodinfo. - Modules can be removed using

modprobe -r [module_name]and loaded back usingmodprobe [module_name].

- Kernel modules currently loaded can be listed using

- Cautionary Note:

- When practicing module management, caution must be exercised to avoid disrupting system stability. Select modules for removal that are not critical to system functionality.

- Third-Party Kernel Modules:

- In most cases, Linux administrators interact with third-party kernel modules provided by external vendors, which are often pre-built and automatically loaded by the distribution.

- Conclusion:

- Understanding kernel modules is crucial for managing system resources and integrating new functionalities without disrupting system operation.

- udev Service:

- udev is the Linux device manager responsible for detecting hardware changes and managing device information. When a new device is connected, udev passes information about it through the dbus service to update the /dev pseudo file system.

- /dev Directory:

- The /dev pseudo file system contains handles to all devices connected to the system. Hardware information, such as CPU, memory, network, and hard drive details, can be found in this directory.

- Handling Hardware Information:

- Various commands can be used to view hardware information from the command line, such as lsblk for block devices, lsusb for USB devices, lspci for PCI devices, and ls cpu for CPU details.

- ls Commands for Hardware Information:

lsblk: Lists block devices and partitions with mount points.lsusb: Displays connected USB devices, including hubs and controllers.lspci: Lists PCI devices and their associated kernel drivers.ls cpu: Provides detailed information about the CPU, including architecture, vendor, model, speed, and supported flags.

- Additional Options:

- These commands offer various options (

-v,-t,-f, etc.) to display more detailed or formatted information about hardware components and their configurations.

- These commands offer various options (

- Practical Exploration:

- Exploring these commands on your system provides valuable insight into the hardware configuration and offers practice in navigating and understanding system resources.

- Conclusion:

- Hardware information in Linux can be easily accessed and viewed from the command line using specific commands, facilitating system administration tasks and troubleshooting.

- Linux Boot Process Overview:

- The boot process starts with the BIOS checking hardware and I/O devices. The bootloader, often GRUB, loads the Linux Kernel, which then initializes an initial RAM disk containing device drivers and mounts the file system from the hard disk.

- Initialization System:

- After setting up the kernel, the initialization system takes over, mounting file systems, loading services (daemons), and preparing the computer for use.

- Boot Logs:

- Boot logs are generated from the Kernel Ring Buffer in RAM and contain system messages. These logs are typically volatile and are lost upon reboot.

- Kernel Ring Buffer:

- The kernel writes system messages to the Kernel Ring Buffer, which can be viewed using utilities like

dmesgto check hardware recognition and low-level memory management messages.

- The kernel writes system messages to the Kernel Ring Buffer, which can be viewed using utilities like

- journalctl Command:

- On modern Linux distributions with systemd,

journalctlis used to view system logs, including kernel messages. The-koption displays kernel messages similar todmesgoutput, along with additional system event logs.

- On modern Linux distributions with systemd,

- Exploration of Initialization Technologies:

- In upcoming lessons, various initialization technologies used in Linux, including systemd, will be discussed in detail.

- Conclusion:

- Understanding the Linux boot process and boot logs is essential for troubleshooting system issues, checking hardware recognition, and monitoring system events during boot.

- Background on Init:

- Init stands for initialization and is based on the System V init system, originally used in UNIX systems. Sysvinit, written by Miquel van Smoorenburg, is the version used in Linux systems.

- Init System Functionality:

- After the kernel loads, it hands over control to the init program located at

/sbin/init, which reads configuration settings from/etc/inittabto determine the system’s runlevel.

- After the kernel loads, it hands over control to the init program located at

- Runlevels Overview:

- Runlevels are predefined configurations that dictate which services/scripts are started or stopped. Each runlevel serves a specific purpose:

- Runlevel 0: Halt or shutdown

- Runlevel 1: Single-user mode

- Runlevel 2: Multi-user mode without networking

- Runlevel 3: Multi-user mode with networking

- Runlevel 4: Custom runlevel (typically unused)

- Runlevel 5: Multi-user mode with networking and graphical desktop

- Runlevel 6: Reboot

- Runlevels are predefined configurations that dictate which services/scripts are started or stopped. Each runlevel serves a specific purpose:

- Inittab File:

- The

/etc/inittabfile specifies runlevels and associated actions. Each line in the file contains fields for identifier, runlevel, action, and process to execute.

- The

- Initialization Scripts:

- Initialization scripts are located in directories like

/etc/rc.d(Red Hat-based) or/etc/init.d(Debian-based). Scripts in these directories are symbolic links to original script files.

- Initialization scripts are located in directories like

- Runlevel Scripts:

- Runlevel directories (e.g.,

rc0.d,rc1.d) contain symbolic links to scripts in the/etc/init.ddirectory. Scripts are prefixed with ‘K’ (to kill) or ‘S’ (to start), followed by a numerical order.

- Runlevel directories (e.g.,

- rc.sysinit and rc.local:

rc.sysinitperforms system cleanup before entering the runlevel.rc.localexecutes after the runlevel has loaded and is often customized by administrators.

- Understanding Init:

- Knowing how init and runlevels work helps understand system startup processes and the transition to newer initialization systems like systemd.

- Transition to systemd:

- Newer Linux systems use systemd, but understanding init is crucial for historical context and troubleshooting.

- Background on Upstart:

- Developed for Ubuntu by Scott Remnant, Upstart aimed to improve boot time by starting services asynchronously. It introduced real-time events and could monitor and restart services.

- Boot Sequence with Upstart:

- Upstart daemon is named

initto retain compatibility with the kernel. It fires off the startup event, mounts filesystems, loads drivers, and runs scripts likerc-sysinit.confto prepare the system.

- Upstart daemon is named

- Upstart Jobs:

- Events trigger Upstart jobs, which are divided into tasks and services. Tasks execute and return to a waiting state, while services are monitored by Upstart and may be respawned if they fail.

- Job States in Upstart:

- Jobs can be in various states:

- Waiting: Initial state, waiting to do something.

- Starting: Job is about to start.

- Running: Job is actively running.

- Stopping: Job is processing pre-stop configuration.

- Killed: Job is stopping.

- Post-stop: Job has completely stopped and returns to waiting state.

- Jobs can be in various states:

- Respawning:

- Upstart attempts to respawn failed jobs up to 10 times at 5-second intervals before dropping the job entirely.

- Conclusion on Upstart:

- Upstart was a significant improvement over traditional Init, with its ability to handle events and react dynamically to changes in the system. It was widely adopted but has been largely replaced by systemd in modern Linux distributions.

- Transition from Init to systemd:

- systemd replaced many Bash init scripts with faster, compiled C code, improving boot time and efficiency.

- While systemd deprecates older init scripts, it still offers compatibility mechanisms to use them.

- Unit Files in systemd:

- systemd utilizes unit files instead of shell scripts for managing services.

- Unit files are located in

/usr/lib/systemd/system,/etc/systemd/system, and/run/systemd/system. - Use

systemctl list-unit-filesto view all unit files on the system.

- Format of systemd Unit Files:

- Unit files resemble INI files.

- They include directives like

Description,Documentation,Requires,Wants,Conflicts,After, andBefore. - More directives and details can be found in the

systemd.unitman page.

- Viewing Unit Files:

- Use

systemctl catcommand to view the full configuration of a unit file.

- Use

- Systemd Boot Process:

- The kernel looks for

/sbin/initto start the system. - systemd creates a symbolic link from

/sbin/initto itself, allowing it to be invoked by the kernel. - systemd reads its unit files and target units to boot the system and manage services.

- The kernel looks for

- Conclusion:

- Understanding systemd unit files is crucial for managing services and booting a systemd-based Linux system efficiently.

- Review of Run Levels:

- Run levels indicate different system states, such as halt, single user mode, multi-user mode with or without networking, graphical desktop environment, and reboot.

- Run levels are managed differently in classic System V init and Upstart systems.

- Changing Run Levels:

- Use the

telinitorinitcommand followed by the desired run level number to switch run levels. - Requires root privileges.

- Use the

runlevelcommand to verify the current and previous run levels.

- Use the

- Changing Run Levels during Boot:

- Interrupt the boot process to access the GRUB menu.

- Modify kernel arguments to specify the desired run level.

- Useful for temporarily changing run levels without modifying

/etc/inittab. - Verify the run level after booting.

- Shutting Down the System:

- Change the run level to

0to halt the system. - Requires root privileges.

- Change the run level to

- Transition to systemd:

- Most modern Linux distributions use systemd, which manages run levels differently.

- Future lessons will cover how to manage run levels in systemd-based systems.

- Purpose of Target Units:

- Target units synchronize with other units during system boot or state changes.

- They define the operating environment, such as multi-user CLI, graphical desktop, or rescue mode.

- Each target may include associated services, slices, and scopes.

- Common Target Units:

multi-user.target: Similar to runlevel 3, provides a CLI with networking for multiple users.graphical.target: Similar to runlevel 5, provides a graphical desktop environment.rescue.target: Similar to runlevel 1, provides an isolated environment for system repairs.basic.target: Basic system used during boot before switching to the default target.sysinit.target: Starts immediately after systemd takes control from the kernel.

- Target Unit Files:

- Target unit files specify dependencies, requirements, and isolation settings.

- View unit files for targets to understand their configurations and dependencies.

- Managing Target Units:

- Use

systemctl list-unit-filesto view all target unit files and their states. - Use

systemctl list-unitsto view currently active target units. - Check and set the default target with

systemctl get-defaultandsystemctl set-default. - Change to a different target using

systemctl isolate.

- Use

- Isolating Target Units:

- The

allow-isolatedirective in the unit file allows changing to the target. - Isolating a target is similar to changing run levels in traditional systems.

- Changing targets can also be done during system reboot or shutdown.

- The

- Conclusion:

- Target units define system environments and are easily managed in systemd.

- Understanding target units helps configure system behavior effectively.

- Rebooting the System:

- Common commands for rebooting include:

runlevel6: Not recommended for rebooting.reboot: Initiates immediate system reboot.shutdown -r now: Shuts down and restarts the system immediately.systemctl isolate reboot.target: For systemd-based systems, isolates to reboot target.

- It’s advisable to inform other users before rebooting using the

wallcommand.

- Common commands for rebooting include:

- Powering Off the System:

- Commands for shutting down the system:

poweroff: Powers down and halts the system.telinit 0: On older systems, switches to run level 0 and halts the system.shutdown -h: Shuts down and halts the system with a specified delay.

- Commands for shutting down the system:

- Canceling Shutdown:

- You can cancel a pending shutdown using

Ctrl + Cduring the countdown.

- You can cancel a pending shutdown using

- ACPID Overview:

- ACPID (Advanced Configuration Power Interface) registers events related to power management, such as lid closure, power button press, etc.

- Configuration files for ACPID are located in

/etc/acpi. - Events are defined in the

eventsdirectory, while actions are defined in theactionsdirectory. - ACPID handles power-related events and triggers actions accordingly, such as shutting down the system cleanly when the power button is pressed.

- Focus for LPIC-1 Exam:

- Understanding ACPID’s role in power management is essential for the exam, but configuration details are not required.

- ACPID primarily deals with power-related events and actions.

I followed the lab Configuring a Default Boot Target achieved the following learning objectives:

Check the default target

Change the default target

Check the Default Target again

- Main File System Locations:

- Root Directory (

/): The base of the directory tree from which all other directories descend. /varDirectory: Contains variable data such as log files, email files, and dynamic content./homeDirectory: User’s home directory where personal files are stored, each user gets their own directory./bootDirectory: Contains Linux kernel and supporting files necessary for booting the system./optDirectory: Used for optional software from third-party vendors in enterprise environments.- Swap Space: Temporary storage acting like RAM, used when physical RAM is full. Can be a swap partition or a swap file.

- Root Directory (

- Swap Sizing:

- Previously, recommended swap space was 1.5 to 2 times the available RAM, but nowadays it’s more flexible.

- Generally, not less than 50% of available RAM is recommended for swap space.

- Partitioning and Mount Points:

- Partitions divide the hard disk into separate sections, each serving a specific purpose.

- Mount points associate partitions with specific directories in the file system hierarchy.

- Example:

/dev/sda1mounted to/root,/dev/sda2mounted to/home, etc.

- Commands for Viewing Disk Information:

mount: Lists all mounted partitions.lsblk: Lists block devices and their partitions.fdisk -l: Lists partitions on a specific disk.swapon --summary: Displays information about swap space.

- Understanding Disk Naming:

- Disk names like

/dev/sda1indicate the device (sda) and partition number (1). - Naming conventions may vary based on hardware type (e.g., SCSI, IDE, SATA, NVMe).

- Disk names like

- Introduction to Swap:

- Swap can be implemented as a partition or a file, used for virtual memory.

- Swap file is slower than a dedicated swap partition.

- Conclusion:

- Understanding file system locations, partitioning, and swap is essential for the LPIC-1 exam.

- Future lessons will delve deeper into partitioning and file system creation.

- Introduction to LVM:

- LVM stands for Logical Volume Manager, allowing the creation of disk partitions assembled into a single or multiple file systems.

- Flexibility: Supports resizing of volumes, useful for managing disk space efficiently.

- Snapshots: Allows for creating point-in-time copies of logical volumes for backup purposes.

- Logical Volume Group Layout:

- Physical Volumes: Actual disks or partitions (e.g.,

/dev/sda,/dev/sdb,/dev/sdc). - Volume Group (VG): Grouping of physical volumes.

- Logical Volumes (LV): Carved-up portions of volume groups, acting like partitions.

- File Systems: Applied on logical volumes to store data.

- Mount Points: Directories where file systems or logical volumes are mounted.

- Physical Volumes: Actual disks or partitions (e.g.,

- Commands for Viewing LVM Setup:

pvs(Physical Volume Scan): Lists physical volumes.vgs(Volume Group Scan): Lists volume groups.lvs(Logical Volume Scan): Lists logical volumes within volume groups.

- Example LVM Layout:

- Physical Volume:

/dev/vda2 - Volume Group:

VolGroup00 - Logical Volumes:

LogVo00,LogVo01withinVolGroup00. - File Systems: Mount points for logical volumes.

- Physical Volume:

- Understanding LVM for LPIC-1:

- Not necessary to be an expert, but understand basic concepts.

- Commands provided for displaying basic LVM setup on a RHEL 7.4 server.

- Awareness of LVM functionalities such as resizing, snapshots, and logical volume management is sufficient.

- Introduction to Legacy GRUB:

- Legacy GRUB, or Grand Unified Boot Loader, is an older version of GRUB found on older systems.

- Operates in stages, starting with boot.img in the master boot record (Stage 1), followed by core.img (Stage 1.5), and then the boot partition (Stage 2).

- Configuration Files:

/boot/grub/grub.conf(Red Hat-based) ormenu.lst(Debian-based): Contains boot configuration options.device.map: Indicates the drive containing the kernel and the OS to boot.

- Example Configuration File:

- Configuration lines for boot disk, default boot option, timeout, splashimage, kernel details, and initial RAM disk.

- Multiple kernel versions listed for boot selection, allowing fallback options in case of compatibility issues.

- Installing GRUB:

- Use

grub-installcommand followed by the device to install GRUB files. - Location typically

/dev/vda1or(hd0)for the first drive. - Use

findcommand within GRUB shell to locate GRUB files.

- Use

- GRUB Shell Commands:

- Enter GRUB shell by running

grubas root. - Use

helpcommand for a list of available commands. findcommand locates GRUB files, such asstage1.

- Enter GRUB shell by running

- Caution:

- Exercise caution when making changes in the GRUB shell to avoid damaging configuration files.

- Backup GRUB configuration file before making permanent changes.

- Introduction to GRUB2:

- GRUB2 is the newer version of GRUB, designed for modern systems.

- Supports GPT (GUID Partition Table) disks, which offer more partitions and larger sizes compared to MBR disks.

- GPT Partition Tables:

- GPT disks support up to 128 partitions and larger individual partition sizes.

- Requires UEFI (Unified Extensible Firmware Interface) for booting.

- UEFI acts as a modern BIOS replacement and provides security features against unauthorized OS booting.

- Boot Process with GRUB2 on GPT Disk:

- UEFI looks for the master boot record (MBR) to find the bootloader.

- Boot process involves stages similar to Legacy GRUB but adapted for GPT disks and UEFI.

- Core.img looks for the EFI System Partition (ESP) containing boot images.

- GRUB2 Configuration:

- Configuration files located in

/boot/grub2directory. grubenvstores environment settings, while/etc/default/gruballows for modification of options.- Use

grub2-mkconfigto generate a new GRUB configuration file based on changes in/etc/default/grub.

- Configuration files located in

- GRUB2 Commands:

grub2-editenv: Edit environment settings.- Avoid direct editing of files under

/boot/grub2and/boot/grub. - Configuration files under

/etc/grub.d/contain settings read bygrub2-mkconfig.

- Update Process:

- Run

grub2-mkconfigto update GRUB configuration after making changes. - Configuration files should not be directly edited as they are automatically generated.

- Run

- Multi-Boot Configuration:

- Add new menu entries in the configuration file to boot additional operating systems, like Windows.

- Interacting with GRUB Boot Loaders:

Legacy GRUB:

- Boot Process:

- Press any key to enter GRUB menu.

- Use arrow keys to select kernel or press A to add arguments.

- Edit boot line by removing or adding options.

- Press Enter to boot selected kernel.

- Changing Runlevels:

- Press A to append an option to boot into a specific runlevel.

- GRUB Command Line:

- Press C to access GRUB command line.

- Use commands like

help,install, orsetupto manage GRUB.

- Reinstalling GRUB:

- Use

setupcommand to automatically reinstall GRUB to the master boot record. - Reboot to ensure successful installation.

- Use

GRUB 2:

- Boot Process:

- Press E to edit boot options before booting.

- Edit configuration options directly.

- Use systemd specific commands for changing targets.

- Press F10 or ctrl+X to boot edited configuration.

- GRUB Command Line:

- Press C to access GRUB command line.

- Use commands like

lsto list available drives and partitions.

- Manually Booting with GRUB:

- Set root drive and kernel using commands like

rootandlinux. - Specify root partition for Linux kernel using

root=option. - Set initial RAM disk using

initrdcommand. - Boot configured system using

bootcommand.

- Set root drive and kernel using commands like

Conclusion:

- Understanding Boot Processes:

- Legacy GRUB offers simpler interaction but limited options.

- GRUB 2 provides more flexibility but requires understanding of systemd and different command syntax.

- Practical Exercise:

- Manually booting with GRUB helps understand the boot process thoroughly.

- Managing Shared Libraries:

Understanding Shared Libraries:

- Definition:

- Shared libraries contain functionality used by multiple applications.

- They prevent redundancy in programming by allowing applications to call common functions.

- File Extensions:

- Shared libraries have a .so (shared object) extension.

- Statically linked libraries end with .a.

Locations of Shared Libraries:

- Common Locations:

- /lib or /usr/lib (32-bit systems).

- /usr/lib64 (64-bit systems).

- /usr/local/lib and /usr/share.

Commands and Configuration Options:

- Checking Linked Libraries:

- Use

lddcommand followed by program name to see linked libraries.

- Use

- Building Library Cache:

ldconfigcreates a cache of recently used libraries.- It reads configuration files from /etc/ld.so.conf.d.

- Requires root privileges to rebuild cache.

- Configuration File for ldconfig:

- Configuration files are found under /etc/ld.so.conf.d.

- Use .conf extension for these files.

- Using Environment Variables:

LD_LIBRARY_PATHspecifies additional library directories.- Useful for temporarily testing new library locations.

- Best practice is to use ldconfig for permanent configurations.

Conclusion:

- Efficient Library Management:

- Shared libraries reduce redundancy and improve system predictability.

- Proper configuration ensures applications can access necessary libraries.

- Best Practices:

- Use ldconfig for permanent configurations.

- LD_LIBRARY_PATH can be used for temporary adjustments.

- Advanced Package Tool (APT):

Introduction to APT:

- Functionality:

- Default package tool for Debian-based systems (e.g., Ubuntu, Linux Mint).

- Installs applications and their dependencies.

- Handles updates, upgrades, and removal of packages.

- Comparison with dpkg:

- APT installs package dependencies automatically, unlike dpkg.

Components and Commands:

- /etc/apt/sources.list File:

- Contains URLs of software repositories.

- Lists packages available for installation.

- Updating the APT Cache:

- Use

sudo apt-get updateto update the local APT cache. - APT cache stores package listings, improving installation speed.

- Use

- Upgrading Packages:

sudo apt-get upgradeupgrades packages to the latest versions.sudo apt-get dist-upgradeupgrades the distribution to the latest level.

- Installing and Removing Packages:

sudo apt-get install [package]installs a package and its dependencies.sudo apt-get remove [package]removes a package but retains dependencies.sudo apt autoremoveremoves unused dependencies.sudo apt-get purge [package]removes package and its configuration files.

- Downloading Packages:

- Use

apt-get download [package]to download a package without installing it.

- Use

- Searching and Getting Information:

apt-cache search [keyword]searches for packages related to the keyword.apt-cache show [package]provides detailed information about a package.apt-cache showpkg [package]displays repository information and dependencies.

Conclusion:

- Efficient Package Management:

- APT simplifies package installation, upgrade, and removal.

- Automatically handles dependencies, improving system stability.

- Usage Examples:

- Updating and upgrading packages using

apt-get. - Installing, removing, and purging packages.

- Searching for and obtaining information about packages.

- Updating and upgrading packages using

- Debian Package Tool (dpkg):

Introduction to dpkg:

- Functionality:

- Works with .deb packages.

- Installs, analyzes, and removes packages.

- Provides information about installed packages.

Commonly Used dpkg Commands:

dpkg --info [package]:- Displays basic information about a package.

dpkg --status [package]:- Shows status information about an installed package.

dpkg -l:- Lists all installed packages with basic information.

- Installing and Removing Packages:

- Installation:

sudo dpkg -i [package.deb] - Removal:

sudo dpkg -r [package] - Purge:

sudo dpkg -P [package]

- Installation:

dpkg -L [package]:- Lists files installed by a package.

- Searching for Packages:

- Search:

dpkg -s [keyword]

- Search:

- Reconfiguring Packages:

- Reconfigure:

sudo dpkg-reconfigure [package] - Used to modify package configurations.

- Reconfigure:

Example Usage:

- Analyzing and Installing Packages:

- Viewing package information with

dpkg --info. - Installing packages with

dpkg -i.

- Viewing package information with

- Managing Installed Packages:

- Listing installed packages with

dpkg -l. - Removing packages with

dpkg -rand purging with-P.

- Listing installed packages with

- Reconfiguring Packages:

- Modifying package configurations using

dpkg-reconfigure.

- Modifying package configurations using

Conclusion:

- Efficient Package Management:

- dpkg is essential for managing .deb packages on Debian-based systems.

- Provides detailed information and control over installed packages.

- Usage Examples:

- Analyzing, installing, and removing packages.

- Listing installed packages and their files.

- Reconfiguring package settings.

- Yellowdog Updater Modified (yum):

Introduction to yum:

- Origin and Purpose:

- Originally used for Yellowdog Linux distribution.

- Handles RPM dependencies, avoiding “dependency hell.”

- Commonly used on RedHat-based systems: RedHat Enterprise Linux, CentOS, Scientific Linux, older Fedora versions.

- Basic Setup:

- Global configuration: /etc/yum.conf.

- Repository configuration: /etc/yum.repos.d/.

- Caches repository information in /var/cache/yum.

- Comparison with Other Package Managers:

- Zypper: SUSE Linux.

- DNF (Dandified yum): Modern Fedora Linux distributions.

Usage and Commands:

- Updating Packages:

yum update: Searches for and installs available updates.

- Searching and Installing Packages:

yum search [keyword]: Searches for packages.yum install [package]: Installs a package.

- Viewing Package Information:

yum info [package]: Displays information about a package.

- Listing Installed Packages:

yum list installed: Lists all installed packages.

- Cleaning Up:

yum clean all: Cleans yum cache and metadata.

- Removing Packages:

yum remove [package]: Removes a package.

- Automatic Removal of Unused Packages:

yum autoremove: Removes packages no longer needed.

- Finding Packages Providing Specific Files:

yum whatprovides [file]: Finds packages containing specified files.

- Reinstalling Packages:

yum reinstall [package]: Reinstalls a package.

- Downloading Packages:

yumdownloader [package]: Downloads a package without installing it.

Conclusion:

- Efficient Package Management:

- yum simplifies package installation, removal, and upgrades.

- Handles dependencies automatically.

- Commonly Used Commands:

- Update, install, remove, search, info.

- Key Locations and Configuration Files:

- /etc/yum.conf, /etc/yum.repos.d/.

- Future Developments:

- DNF expected to replace yum in RedHat Enterprise Linux.

- Red Hat Package Manager (rpm):

Introduction to rpm:

- Purpose and Functionality:

- Similar to Debian packages (

.deb) for managing software on Linux systems. - Contains application/utilities, default configuration files, installation instructions, and dependencies.

- Uses an rpm database located at

/var/lib/rpm.

- Similar to Debian packages (

- Handling Dependencies:

- Dependencies must be installed or resolved manually.

yumon Red Hat-based systems handles dependencies automatically.

Basic Commands and Usage:

- Querying Package Information:

rpm -qi [package.rpm]: Displays information about an rpm package.

- Listing Files in a Package:

rpm -ql [package.rpm]: Lists files contained within an rpm package.

- Listing Installed Packages:

rpm -qa: Lists all installed packages.

- Installing Packages:

sudo rpm -ivh [package.rpm]: Installs an rpm package.

- Upgrading Packages:

sudo rpm -Uvh [package.rpm]: Upgrades an rpm package to a newer version.

- Removing Packages:

sudo rpm -e [package]: Removes an rpm package from the system.

Maintenance and Advanced Usage:

- Database Repair:

rpm --rebuilddb: Rebuilds the rpm database if corrupted.

- Comparing Installed Files:

rpm -Va: Compares installed files with rpm database for integrity.

- Converting rpm to cpio:

rpm2cpio [package.rpm] | cpio -idmv: Extracts contents of an rpm package.- Useful for accessing files within the package or for customizing package contents.

Conclusion:

- Efficient Package Management:

- rpm provides a way to manage software packages on Red Hat-based systems.

- Offers commands for querying, installing, upgrading, and removing packages.

- Database Maintenance:

- Commands like

--rebuilddband-Vahelp ensure the integrity of the rpm database.

- Commands like

- Advanced Usage:

rpm2cpioallows extracting contents of rpm packages for customization or inspection.

- Key Locations and Concepts:

/var/lib/rpm: Location of the rpm database.- Dependency management: Handled by

yumon Red Hat-based systems.

Notes: Installing and Managing Packages on Ubuntu/Debian Linux

ABOUT THIS LAB

- Objective: Installation and removal of packages using

aptanddpkg. - Platform: Ubuntu 16.04 LTS system.

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

- Install the Apache Web Server Package.

- Verify the Server is Running and Capture the Result.

Scenario

- Task: Provision an Ubuntu 16.04 LTS server for basic web server testing.

- Requirement: Install Apache web server package (

apache2) and ensurewgetpackage is installed. - Action: Download the default web page from the Apache server and save it to

local_index.result. - Next Step: Turn the system over to the developers after completing the tasks.

Procedure

Install the Apache Web Server Package

1

2

3

4

sudo apt install apache2 wget

sudo apt update

sudo systemctl status apache2

wget --output-document=local_index.response http://localhost

Notes: Installing and Managing Packages on Red Hat/CentOS Systems

ABOUT THIS LAB

- Objective: Installation and removal of packages using

yumandrpm. - Platform: Red Hat/CentOS Linux distributions.

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

- Install Available Elinks Application.

- Verify Elinks Package RPM Exists.

Scenario

- Task: Resolve missing dependencies to install the

elinkspackage. - Requirement: Install

elinkspackage from a downloaded .rpm file in the/home/cloud_user/Downloadsdirectory. - Action: Resolve dependencies using

yumand installelinkspackage. Verify the application is installed and running properly.

Solution

- Install Available Elinks Application

- View contents of the current directory:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

ls -la

cd Downloads/

ls -la

sudo rpm -i elinks-0.12-0.37.pre6.el7.0.1.x86_64.rpm

sudo yum install js

sudo yum install nss_compat_ossl

sudo rpm -i elinks-0.12-0.37.pre6.el7.0.1.x86_64.rpm

sudo rpm -i elinks-0.12-0.37.pre6.el7.0.1.x86_64.rpm

elinks

Virtualization:

- Definition and Purpose:

- Emulates specific computer systems within another.

- Allows running multiple operating systems on the same physical hardware.

- Utilizes a hypervisor to manage communication between virtual machines and host OS.

- Types of Virtualization:

- Full Virtualization: Guest OS unaware it’s running on a VM.

- Paravirtualization: Guest OS aware, uses guest drivers for improved performance.

Virtual Machines:

- Creation and Management:

- Can be cloned or turned into templates for rapid deployment.

- D-Bus machine ID ensures uniqueness to prevent conflicts.

Virtual Machines in Cloud:

- Cloud Provisioning:

- Cloud providers offer virtual servers for easy provisioning.

cloud-initcommand ensures new VMs have unique settings.

Containers:

- Definition and Types:

- Isolated sets of packages, libraries, and/or applications.

- Machine Containers: Share kernel and file system with the host.

- Application Containers: Share everything except application and library files.

Container Technologies:

- Examples:

- Docker, systemd’s nspawn, LXD, OpenShift.

- Provide dynamic allocation and management of containers.

Comparison with Virtualization:

- Resource Utilization:

- Virtualization: Emulates virtual hardware, heavier resource usage.

- Containers: Utilize existing OS, more efficient resource management.

Conclusion:

- Purpose and Efficiency:

- Virtualization enables running multiple OS instances on the same hardware.

- Containers offer lightweight, isolated environments for applications.

- Resource Management:

- Virtualization provides segregation of resources for different OS instances.

- Containers offer granular management of system resources, efficient utilization.

- Shell Overview and Bash Shell:

Shell Types:

- Definition:

- Command line environment in Linux.

- Not the GUI interface, but the text-based interface.

- Types:

- Bash Shell (Default)

- C Shell

- Korn Shell

- Z Shell

Bash Shell:

- Components:

- Environment Variables: Settings dictating common functionality and locations.

- Functions: Defined using the

functionkeyword.

- Viewing Environment Variables:

envorenvironmentcommand.echo $VARIABLE_NAMEto see a specific variable.setcommand to view all environment variables and functions.

- Debugging:

set -xto turn on debugging,+xto turn off.

- Creating and Removing Functions:

unset -f FUNCTION_NAMEto remove a function.

- Modifying Shell Options:

shoptcommand to view and set shell options.

- Exporting Variables:

export VARIABLE_NAME=valueto make variable available in child shells.

- Other Useful Commands:

pwd: Print working directory.which: Show location of a command.type: Show type of command (built-in, function, or external).

- Quoting:

- Double quotes for weak quoting (allows variable expansion).

- Single quotes for strong quoting (treats content literally).

Conclusion:

- Bash Shell is the default command line environment in Linux.

- Understanding environment variables, functions, and shell options is essential for efficient shell usage.

Quoting is important in shell scripting to control variable expansion.

- Bash History and Manual Pages:

Bash History:

- History Command:

- Displays recently run commands in numerical order.

- Use Up and Down Arrow keys to scroll through history.

- Referencing commands using

!followed by command number.

- History File:

- Stored in

.bash_historyin user’s home directory. - Hidden file, viewable with

ls -a. - Records commands based on

HISTFILESIZEenvironment variable.

- Stored in

- Usage:

history: Display history.!n: Repeat command numbern.

Manual Pages:

- Usage:

man command: Open manual page for a command.- Sections:

- 1: Executable programs and shell commands.

- 2: System calls.

- 3: Library calls.

- 4: Special files.

- 5: File formats and conventions.

- 6: Games.

- 7: Miscellaneous.

- 8: System administrator commands.

- 9: Non-standard kernel routines.

- Navigate using Up/Down Arrow keys or J/K keys (similar to Vim).

- Quit with

q.

- Searching:

man -k keywordorapropos keyword: Search all manual pages for a keyword.

- Viewing Specific Sections:

- Use

man section commandto view a specific section of a command’s manual page. - Section numbers denote the type of information provided.

- Use

Conclusion:

- Understanding Bash history helps navigate past commands efficiently.

- Manual pages provide detailed documentation for commands, configurations, and system tasks.

- Sections in manual pages help organize information based on relevance.

Searching and viewing specific sections of manual pages is essential for finding relevant information quickly.

- Viewing Text Files:

Basic Commands:

- Cat Command:

- Used to view text files.

- Can concatenate files together.

cat file1 file2: Concatenate files.

- Less Command:

- Read-only viewing of text files.

- Allows paging up and down.

- Search functionality (

/)./search_term: Search for term.n: Navigate to next instance.P: Navigate to previous instance.

- Quit with

q.

- Head Command:

- Display first lines of a file.

head file: Display first 10 lines.head -n N file: Display first N lines.

- Display first lines of a file.

- Tail Command:

- Display last lines of a file.

tail file: Display last 10 lines.tail -n N file: Display last N lines.

- Useful for following log files (

tail -f).

- Display last lines of a file.

Compressed Files:

- zcat Command:

- View contents of gzip compressed files.

zcat file.gz.

- View contents of gzip compressed files.

- bzcat Command:

- View contents of bzip2 compressed files.

bzcat file.bz2.

- View contents of bzip2 compressed files.

- xzcat Command:

- View contents of XZ compressed files.

xzcat file.xz.

- View contents of XZ compressed files.

Conclusion:

- Understanding basic text file viewing commands is essential for navigating and inspecting files in the command line.

- Commands like

cat,less,head, andtailoffer different functionalities for reading and manipulating text files efficiently. - Compressed file viewing commands like

zcat,bzcat, andxzcatallow you to view contents without decompressing the files. These commands serve as foundational tools for text file manipulation and analysis, which will be explored further in subsequent lessons.

- Basic File Statistics and Integrity Checking:

Number of Lines and Words:

- Number of Lines:

- Use

wc -l filenameto count lines.-boption includes blank lines.

- Use

- Number of Words:

- Use

wc -w filenameto count words. - Each word is counted, including special characters.

- Use

Octal Dump (od) Command:

- View file contents in octal format.

- Use

od filename. -coption for character format.- Useful for troubleshooting and identifying unexpected characters.

- Use

Message Digest (Hash) Checking:

- MD5 Hash:

- Generate MD5 hash:

md5sum filename. - Store hash in file:

md5sum filename > filename.md5. - Check file integrity:

md5sum -c filename.md5.

- Generate MD5 hash:

- SHA256 Hash:

- Generate SHA256 hash:

sha256sum filename. - Store hash in file:

sha256sum filename > filename.sha256. - Check file integrity:

sha256sum -c filename.sha256.

- Generate SHA256 hash:

- SHA512 Hash:

- Generate SHA512 hash:

sha512sum filename. - Store hash in file:

sha512sum filename > filename.sha512. - Check file integrity:

sha512sum -c filename.sha512.

- Generate SHA512 hash:

Conclusion:

- Basic file statistics commands like

wcprovide information on lines, words, and bytes. - Octal dump (

od) command displays file contents in octal or character format, aiding in troubleshooting. - Message digest (hash) functions like MD5, SHA256, and SHA512 ensure file integrity and are useful for verifying downloads or detecting file modifications.

- Hash values can be stored in files for future verification using the

-coption with the respective hash command. Verifying file integrity using hash values is essential for ensuring data integrity and security.

- Text File Modification Commands:

Sort Command:

- Sorts file contents alphabetically or numerically.

- Basic sorting:

sort filename. - Numerical sorting:

sort -n filename. - Sorting based on a specific column:

sort -t',' -k2 filename.

- Basic sorting:

Unique Command:

- Prints unique lines of a file.

- Basic unique output:

uniq filename. - Count occurrences of unique lines:

uniq -c filename. - Display unique groups:

uniq --group filename.

- Basic unique output:

Translate (tr) Command:

- Translates characters in a file.

- Swap commas with colons:

cat filename | tr ',' ':'. - Delete specified characters:

cat filename | tr -d ','. - Convert uppercase to lowercase:

cat filename | tr 'A-Z' 'a-z'.

- Swap commas with colons:

Cut Command:

- Extracts specific columns from a file.

- Specify delimiter:

cut -d',' -f3 filename. - Print multiple columns:

cut -d',' -f2,3 filename.

- Specify delimiter:

Paste Command:

- Combines contents of two files.

- Parallel combination:

paste file1 file2. - Change delimiter:

paste -d',' file1 file2. - Serial combination:

paste -s -d',' file1 file2.

- Parallel combination:

Conclusion:

- These commands are essential for text file manipulation and processing.

- Sort, uniq, tr, cut, and paste are powerful tools for organizing, filtering, and transforming text data.

Understanding these commands is crucial for system administrators and users dealing with text-based data processing tasks.

- Additional Text Manipulation Commands:

Sed Command:

- Stream editor used for text manipulation.

- Basic search and replace:

sed 's/original/new/g' filename. - In-place editing:

sed -i 's/original/new/g' filename. - Replace globally:

sed 's/original/new/g' filename.

- Basic search and replace:

Split Command:

- Splits a file into multiple pieces.

- Default split:

split filename. - Specify split size:

split -b 100 filename. - Specify number of output files:

split -n2 filename. - Change output file naming convention:

split -d filename. - Concatenate split files:

cat file* > newfile.

- Default split:

Conclusion:

- Sed offers powerful text manipulation capabilities, including search and replace functionality.

- Split command is useful for dividing large files into smaller chunks.

- Understanding these commands provides flexibility in text processing tasks, essential for system administrators and users.

Notes: Modifying Text File Using sed

ABOUT THIS LAB

- Objective: Modify a text file using

sedto replace instances of ‘cows’ with ‘Ants’. - Scenario: Correct the text file containing the fable of “The Ants and the Grasshopper”.

- Learning Objectives:

- Use

sedto Change a Word in the File - Ensure No Other File in the Home Directory

- Use

Introduction

- The text file contains the fable with ‘cows’ instead of ‘ants’.

- We need to replace all instances of ‘cows’ (case insensitive) with ‘Ants’ using

sed.

The File

- Check the contents of the file:

1

2

cat fable.txt

sed -i 's/cows/Ants/Ig' fable.txt

Conclusion

- The

sedcommand efficiently replaces text in the file. Ensure no other files are created during the process.

- File and Directory Management Commands:

ls Command:

- Used to list files and directories.

-a: Show hidden files.-l: Long listing format.-d: Display directory information.

touch Command:

- Modifies a file’s access time or creates a new empty file.

touch filename: Create a new empty file.touch -m filename: Modify a file’s timestamp.

cp Command:

- Copies files or directories.

cp sourcefile destination: Copy file to destination.cp -r sourcedirectory destination: Recursive copy.cp -v source destination: Verbose mode.

rm Command:

- Removes files or directories.

rm filename: Remove a file.rm -i filename: Prompt before removal.rm -f filename: Force removal.rm -r directory: Recursive removal.

mv Command:

- Moves files or directories.

mv source destination: Move file to destination.- Can be used for renaming files.

file Command:

- Determines file type.

file filename: Display file type information.

Conclusion:

- Understanding file and directory management commands is essential for efficient system administration.

- Commands like

ls,touch,cp,rm,mv, andfileoffer powerful capabilities for managing files and directories in Linux systems. Caution should be exercised, especially with commands like

rm -r, which can recursively remove entire directories.- Basic File System Navigation and Management:

cd Command:

- Used to change directories.

cd directory: Change to specified directory.cd ..: Move to parent directory.cd ~: Move to home directory.cd -: Move to the last directory.

ls Command:

- Lists files and directories.

ls: List files in current directory.ls -a: Show hidden files.ls -l: Long listing format.

pwd Command:

- Displays the current working directory.

Relative and Absolute Paths:

- Relative Path: Relative to the current directory.

- Example:

system/to navigate to a subdirectory.

- Example:

- Absolute Path: Specifies the full directory structure.

- Example:

/etc/systemd/to specify a complete path.

- Example:

Directory Creation and Removal:

mkdirCommand:mkdir directory: Create a new directory.mkdir -p parent/subdirectory: Create nested directories.

rmdirCommand:rmdir directory: Remove an empty directory.

rm -r directory: Remove directory and its contents.

Environment Variables:

PATHEnvironment Variable:- Lists directories where executable files are located.

- Allows running commands without specifying full paths.

Running Scripts and Executables:

./script.sh: Execute a script in the current directory.- Scripts in directories listed in

PATHcan be run without specifying full paths.

Conclusion:

- Understanding basic file system navigation and management commands like

cd,ls,pwd,mkdir,rmdir, andrmis essential for effective Linux system administration. - The

PATHenvironment variable simplifies running commands by specifying directories where executable files are located. - Mastery of these commands enhances productivity and efficiency when working in Linux environments.

Lesson Summary: File Archiving and Compression in Linux

Introduction to Archiving:

- Purpose: Archiving simplifies file and folder distribution and saves disk space through compression.

- Command:

ddis used for file conversion and copying, commonly used for backup purposes and creating bootable USB drives.

Using dd Command:

- Syntax:

dd if=input_file of=output_file - Examples:

- Creating bootable USB drives.

- Backing up master boot record (

dd if=/dev/sda of=/tmp/mbr_backup bs=512 count=1). - Generating random files (

dd if=/dev/urandom of=file bs=1K count=10K).

Introduction to tar:

- Purpose: Bundles files and directories into a single archive file.

- Origin: “tar” stands for “tape archive,” initially used for tape backups.

- Command:

tar -c -f archive_name.tar files/directories

Creating and Extracting Tar Archives:

- Creating Tar Archive:

tar -cf archive.tar files/directories - Listing Contents:

tar -tf archive.tar - Extracting Contents:

tar -xf archive.tar

Compression with tar:

- Purpose: Reduces file size and conserves disk space.

- Common Algorithms:

gzip(tar -czf archive.tar.gz files/directories).bzip2(tar -cjf archive.tar.bz2 files/directories).xz(tar -cJf archive.tar.xz files/directories).

Compression Commands:

- gzip:

gzip file(compress) /gunzip file.gz(decompress). - bzip2:

bzip2 file(compress) /bunzip2 file.bz2(decompress). - xz:

xz file(compress) /unxz file.xz(decompress).

Conclusion:

- File archiving and compression are essential skills for managing files and optimizing storage space on Linux systems.

- Understanding commands like

dd,tar, and compression utilities likegzip,bzip2, andxzenhances efficiency and data management capabilities. - Mastery of these techniques is valuable for system administrators and Linux users alike.

Lesson Summary: Mastering the find Command in Linux

Introduction to find Command:

- Purpose: Locate files and directories based on various criteria within a Linux environment.

- Versatility: Can search by name, time of modification, access, type, and more.

- Acting on Results: Can perform actions on the files found, such as deletion, copying, or moving.

Basic Usage:

- Syntax:

find [directory] [options] [criteria] - Example:

find . -name "mc.shell"(Searches for files named “mc.shell” in the current directory).

Searching in Different Directories:

- Use

.for the current directory. - Use

sudoto search directories requiring elevated privileges (e.g., system directories).

Time-Based Searches:

ctime: Searches for files modified within a specified period.- Example:

find . -ctime 1(Files modified within the last 24 hours).

- Example:

atime: Searches for files accessed within a specified period.- Example:

find . -atime 2(Files accessed within the last 48 hours).

- Example:

Comparing Timestamps:

- Can compare file timestamps to find newer or older files.

- Example:

find /home -newer /home/user/passwd(Finds files newer than the “passwd” file).

Searching for Specific Types:

empty: Finds empty files and directories.- Example:

find /home -empty(Finds empty files and directories in the home directory).

- Example:

type: Filters by file type (e.g., directory, regular file).- Example:

find /home -type f(Finds only regular files in the home directory).

- Example:

Acting on Results:

- Use

-execswitch to execute commands on found files.- Example:

find . -empty -exec rm -f {} \;(Deletes empty files in the current directory).

- Example:

Combining Options:

- Combine different options to refine search criteria.

- Example:

find . -name "*.tar.*" -exec cp -v {} /path/to/destination \;(Copies files matching a pattern to a specified directory).

Conclusion:

- The

findcommand is a powerful tool for locating files and directories in a Linux environment. - Understanding its syntax and various options enables efficient file management and automation of tasks.

- Further exploration of

findoptions, such as permissions-related criteria, enhances its utility for system administration and user tasks.

Lesson Summary: Exploring File Globbing in Bash

Introduction to File Globbing:

- Definition: File globbing is a feature in Bash shell that allows users to search for files and directories using wildcard characters.

- Wildcard Characters: Symbols that can represent one or more characters in a file or directory name.

Basics of Wildcard Characters:

*(Asterisk): Matches zero or more characters.- Example:

ls *.txt(Lists all files ending with.txtin the current directory).

- Example:

?(Question Mark): Matches exactly one character.- Example:

ls ??.txt(Lists files with two characters before.txtextension).

- Example:

Advanced Usage:

- Character Ranges: Use square brackets

[ ]to specify a range of characters.- Example:

ls [A-Za-z]*.csv(Lists files starting with uppercase or lowercase letters followed by.csv).

- Example:

- Exclusion: Use

^(caret) inside square brackets to exclude characters.- Example:

ls [^WTJp]*(Lists files excluding those starting with W, T, J, or P).

- Example:

Combining Wildcards:

- Multiple Wildcards: Can combine multiple wildcard characters for complex searches.

- Example:

ls W[wo]*[0-9]?[0-9][0-9]??.*(Matches files with names starting with W or w, followed by ‘o’, then any digit, followed by two optional digits, and any character after that).

- Example:

Globbing on Directory Names:

- Usage in Directories: Wildcard characters can also be used to match directory names.

- Example:

ls important/*(Lists contents of the directory named ‘important’).

- Example:

Conclusion:

- File globbing in Bash provides powerful functionality for searching and matching file and directory names using wildcard characters.

- Understanding how to use wildcard characters effectively allows for efficient file manipulation and navigation in the command line.

- Experimenting with different combinations of wildcard patterns can lead to precise and flexible search results.

ABOUT THIS LAB

A Linux system administrator needs to know how to create files and folders on a computer.

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

- Create the ‘Projects’ Parent Directories

- Create the ‘Projects’ Subdirectories

- Create ‘Projects’ Empty Files for Next Step

- Rename a ‘Projects’ Subdirectory

Creating a Directory Structure in Linux

Create the Parent Directories

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

mkdir -p Projects/{ancient,classical,medieval}

mkdir Projects/ancient/{egyptian,nubian}

mkdir Projects/classical/greek

mkdir Projects/medieval/{britain,japan}

touch Projects/ancient/nubian/further_research.txt

touch Projects/classical/greek/further_research.txt

mv Projects/classical Projects/greco-roman

ABOUT THIS LAB

Each candidate for the LPIC-1 or CompTIA Linux+ exam needs to understand how to work with various types of compressed files, or “tarballs” as they are commonly known. We will practice with various compression tools and compare the differences between them.

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

- Try out different compression methods

- Create tar files using the different compression methods.

- Practice reading compressed text files.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

ls -lh junk.txt

gzip junk.txt

ls -lh

gunzip junk.txt.gz

bzip2 junk.txt

ls -lh junk.txt.bz2

bunzip2 junk.txt.bz2

xz junk.txt

ls -lh

unxz junk.txt.xz

tar -cvzf gztar.tar.gz junk.txt

tar -cvjf bztar.tar.bz2 junk.txt

tar -cvJf xztar.tar.xz junk.txt

ls -lh

cp /etc/passwd .

tar -cvjf passwd.tar.bz2 passwd

bzcat passwd.tar.bz2

tar -cvzf passwd.tar.gz passwd

zcat passwd.tar.gz

tar -cvJf passwd.tar.xz passwd

xzcat passwd.tar.xz

Lesson Summary: Understanding Standard Input, Output, and Error in Bash

Introduction:

- Standard input (stdin), standard output (stdout), and standard error (stderr) are fundamental concepts in UNIX-like operating systems.

- These streams facilitate communication between processes, files, and the user.

Standard Output (stdout):

- Definition: The default destination for output produced by a command or process.

- Representation: Often abbreviated as

STDOUT. - Usage: Information processed by the computer is sent to stdout, typically displayed on the screen.

- Redirecting stdout: Use the

>character to redirect stdout to a file instead of the screen.

Standard Input (stdin):

- Definition: The default source of input for a command or process, usually from the keyboard.

- Representation: Abbreviated as

STDIN. - Usage: Commands receive input from stdin, either from user keyboard input or from files or output of other commands.

- Redirecting stdin: Use the

<character to redirect input from a file to a command.

Standard Error (stderr):

- Definition: A separate output stream used for error messages and diagnostics.

- Representation: Often abbreviated as

STDERR. - Usage: Error messages are typically displayed on the screen, but can be redirected like stdout.

- Redirecting stderr: Use the

2>character to redirect stderr to a file or another destination. - Combining stdout and stderr redirection: Use

2>&1to redirect stderr to the same destination as stdout.

File Handle Numbers:

- Each stream (stdin, stdout, stderr) is associated with a file handle number.

- stdin: File handle 0

- stdout: File handle 1

- stderr: File handle 2

- File handle numbers are used in redirection operations.

Practice Recommendations:

- Experiment with redirection operations to gain proficiency.

- Practice redirecting different types of output (stdout, stderr) to files, other commands, or both.

- Familiarize yourself with file handle numbers and their usage in redirection.

Conclusion:

- Understanding stdin, stdout, and stderr is crucial for effective command-line usage and shell scripting.

- Redirecting these streams allows for flexible handling of input, output, and error messages.

- Regular practice and experimentation are key to mastering redirection techniques in Bash.

Lesson Summary: Advanced Usage of tee and xargs Commands in Bash

Introduction:

- In this lesson, we explored advanced usage of the

teeandxargscommands in Bash. - These commands offer powerful capabilities for redirecting output and processing data efficiently.

Using tee Command:

- Purpose: Redirects standard output from a command to both a file and the screen simultaneously.

- Syntax:

command | tee filename - Example:

ls -ld user/shared/doc/live[Xx]* | tee live-docs.txt - Usage: Helpful for monitoring output while saving it to a file for later processing.

Exploring xargs Command:

- Purpose: Executes a command with arguments taken from standard input.

- Syntax:

command1 | xargs command2 - Example 1:

find directory -type f -empty | xargs rm- Deletes empty files in a directory more efficiently than using

-exec.

- Deletes empty files in a directory more efficiently than using

- Example 2:

grep -l 'pattern' * | xargs -I {} mv {} directory- Searches for files containing a pattern and moves them to a specified directory.

- Usage: Useful for executing commands on multiple files efficiently.

Comparison with -exec Option:

- -exec Option: Processes files one at a time, can be slow for large sets of files.

- xargs Command: Handles files in batches, more efficient for processing large numbers of files.

Advanced Example with xargs and grep:

- Scenario: Moving files containing specific content to a backup directory.

- Command:

grep -l 'pattern' * | xargs -I {} mv {} backup_directory - Usage: Demonstrates how xargs efficiently handles output from grep for batch processing.

Conclusion:

teeandxargsare powerful commands for redirecting output and processing data efficiently in Bash.- Understanding their usage can lead to more effective command-line operations.

- Practice using these commands in various scenarios to become proficient.

- Mastery of

teeandxargsenhances productivity and problem-solving capabilities in shell scripting and command-line usage.

Lesson Summary: Understanding Processes in Linux

Introduction:

- This lesson explores the basics of how processes work on a Linux system.

What is a Process?

- A process is a set of instructions loaded into memory, derived from a running program.

- It includes components like memory context, priority, and environment.

Process Hierarchy:

- Linux boots with PID 1, usually systemd, which acts as the parent process.

- All other processes are child processes, some of which may spawn further child processes.

- The hierarchy can be viewed using the

pscommand.

Viewing Processes:

- The

pscommand displays processes in the current shell by default. - Options like

-u,-e,-f,--forestprovide different views of processes. - Process information is obtained from the

/procdirectory, which communicates with the Linux kernel.

Real-Time Process Monitoring:

- The

topcommand provides near real-time process information. - Processes can be stopped using the

killcommand, often used to terminate hung or resource-consuming programs.

Conclusion:

- Understanding processes is essential for managing system resources and troubleshooting.

- Linux provides various commands like

ps,top, andkillfor process management. - Practice monitoring and managing processes to effectively maintain system performance and stability.

Lesson Summary: Monitoring and Controlling Processes in Linux

Introduction:

- This lesson covers various commands and techniques for monitoring and controlling processes in Linux systems.

System Uptime and Load:

- The

uptimecommand displays system uptime, current users, and load averages. - Load averages represent the average number of processes in a runnable or uninterruptible state over different time intervals.

Memory Monitoring:

- The

freecommand provides information about available memory and swap space. - Swap space is used as temporary storage when RAM is full.

Process Listing:

- The

pgrepcommand lists process IDs (PIDs) based on name or other criteria. - Process details can be viewed with the

-aswitch. - Process listing can also be filtered by user.

Process Control and Signals:

- Process control involves managing processes using signals.

- Common signals include SIGTERM (15) for graceful shutdown and SIGKILL (9) for forceful termination.

- Process signals can be viewed in the signal man pages (

man 7 signal).

Killing Processes:

- The

killcommand is used to send signals to processes, terminating or controlling their behavior. - Processes can be killed by PID or process name using

pkill. pkill -xensures exact process name matching.

Conclusion:

- Monitoring and controlling processes is essential for system administration and troubleshooting.

- Understanding system load, memory usage, and process behavior helps optimize system performance and stability.

- Proper use of process control commands ensures efficient resource management and problem resolution in Linux systems.

Lesson Summary: Managing Processes in Linux - Part 2

Introduction:

- This lesson covers advanced techniques for managing processes in Linux systems, including killing processes, monitoring commands with

watch, and working with session managers likescreen,tmux, andnohup.

Killing Processes:

- The

killallcommand kills all processes with a specified name. - Specific signals can be sent to processes using the

-sswitch.

Monitoring Commands with watch:

- The

watchcommand periodically reruns a specified command and displays its output. - The default interval is 2 seconds, but it can be changed with the

-noption.

Session Managers:

screenallows users to start a session, run commands, detach from the session, and reattach later.- Commands within a

screensession continue running even after detaching. screen -lslists activescreensessions, andscreen -rreattaches to a specified session.tmuxprovides similar functionality toscreenand is becoming more popular.tmuxsessions can be managed similarly toscreensessions.

Running Commands in the Background with nohup:

nohupallows commands to continue running even after closing the terminal.- Commands can be sent to the background with

&. jobslists background jobs, andfgbrings a background job to the foreground.- Background jobs can be resumed with

bg, and terminated withkill.

Conclusion:

- These advanced process management techniques are valuable for system administrators and users who need to manage long-running tasks, monitor command output, and maintain session continuity across terminal sessions.

- Understanding how to kill processes, monitor commands, work with session managers, and run commands in the background enhances efficiency and productivity in Linux environments.

Lesson Summary: Understanding and Modifying Process Priorities

Introduction:

- Process priorities dictate how much CPU time each process receives.

- Priorities are assigned numerical values known as nice levels, ranging from -20 to 19.

- Lower nice levels (-20 to 0) indicate higher priority, while higher nice levels (1 to 19) indicate lower priority.

Process Priorities:

- Processes typically start with a nice level of 0.

- Only privileged users (root or users with sudo access) can decrease a process’s nice level to increase its priority.

- Regular users can increase a process’s nice level to decrease its priority, promoting fairness in CPU resource allocation.

Commands for Modifying Priorities:

- Use

niceto start a process with a specific nice level. - Use

reniceto modify the nice level of an already running process. renicerequires root privileges to decrease a process’s nice level (increase its priority), but any user can increase the nice level (decrease priority).

Viewing and Modifying Process Priorities:

- Use

pswith appropriate options to view process details, including nice levels. - Use

topto interactively view and manage process priorities. - In

top, use theRkey to renice a process, providing the PID and desired nice level.

Conclusion:

- Understanding process priorities is essential for managing system resources efficiently.

- Modifying process priorities allows users to optimize CPU resource allocation based on application requirements and system load.

- Properly adjusting process priorities promotes fairness and prevents resource contention in multi-user environments.

Lesson Summary: Introduction to Regular Expressions

Overview:

- Regular expressions (regex) are powerful patterns used for searching and manipulating text.

- They differ from file globbing and have distinct characters and syntax.

- Understanding regular expressions is essential for efficient text processing tasks.

Commonly Used Regular Expressions:

- Dot

.:- Matches any single character.

- Used as a placeholder.

- Example:

G.Mmatches words with “G” as the first letter, “M” as the third letter, and any character in between.

- Caret

^:- Matches the start of a line.

- Used to anchor searches at the beginning of lines.

- Example:

^RPCmatches lines starting with “RPC” in the passwd file.

- Dollar

$:- Matches the end of a line.

- Used to anchor searches at the end of lines.

- Example:

Bash$matches lines ending with “Bash” in the passwd file.

- Brackets

[]:- Matches any character within the brackets.

- Can specify a range or list of characters.

- Example:

[va]matches lines containing either “v” or “a”.

- Star

*:- Matches zero or more occurrences of the preceding character or pattern.

- Example:

V*A*Rmatches lines containing “VAR”, “VRR”, “VARR”, etc.

Practice and Further Learning:

- Practice using regular expressions with tools like

grepandsed. - Consult the study guide and man pages (section 7) for more in-depth understanding and practice.

- Regular expressions require practice to master, so keep experimenting to improve proficiency.

Conclusion:

- Regular expressions are essential for text processing tasks in Linux.

- Understanding their syntax and common patterns is crucial for effective use.

- Regular expressions offer powerful capabilities for searching, matching, and manipulating text data.

Lesson Summary: Commands with Regular Expressions

Overview:

- Regular expressions (regex) can be employed in various commands to search, filter, and manipulate text in files.

- Commands like

sed,egrep, andfgrepallow for efficient text processing using regular expressions.

sed Command:

sedcan act on regular expressions to search and manipulate text in files.- Example:

sed '/nologin$/p' /etc/passwdprints lines ending with “nologin” from passwd file. - Example:

sed '/nologin$/d' /etc/passwd > filter.txtfilters lines not ending with “nologin” to a new file.

egrep Command:

egrep(extended grep) implicitly enables extended regular expressions.- Example:

egrep 'Bash$' /etc/passwdprints lines ending with “Bash”. - Example:

egrep -c 'Bash$' /etc/passwdcounts lines ending with “Bash”. - Example:

egrep '^rpc|nologin$' /etc/passwdsearches for lines starting with “rpc” or ending with “nologin”.

fgrep Command:

fgrep(fixed grep) searches for fixed strings using file globbing.- Example:

fgrep -f strings /etc/passwdsearches passwd file for strings listed in the “strings” file. - Example:

fgrep -f strings passwd*searches multiple passwd files for the same strings.

Conclusion:

- Commands like

sed,egrep, andfgrepprovide powerful text processing capabilities using regular expressions. - Regular expressions enable precise search patterns, enhancing efficiency in text manipulation tasks.

- Understanding how to leverage regular expressions in various commands is essential for effective text processing in Linux environments.

Lab Summary: Working with Basic Regular Expressions

About This Lab:

This lab focuses on practicing the use of regular expressions (regex) in Linux system administration tasks. It covers tasks such as locating HTTP and LDAP services in system files using grep with regex patterns and redirecting output to create new files.

Learning Objectives:

- Use regular expressions to locate information on HTTP services.

- Use regular expressions to find port information for LDAP services.

- Create a new file based on HTTP services data.

Task Breakdown:

- Locate HTTP Services:

- Use

grepwith regex to extract lines from/etc/servicesstarting withhttpbut not ending withx. - Redirect output to create a file

http-services.txtin the user’s home directory.

- Use

- Locate LDAP Services:

- Use

grepwith regex to find lines in/etc/servicesstarting withldapand having the fifth character alphanumeric, excluding lines where the sixth character is ‘a’. - Redirect output to create a file

lpic1-ldap.txtin the user’s home directory.

- Use

- Refine the HTTP Results:

- Read

http-services.txtand remove lines ending with the word ‘service’. - Redirect refined output to create a new file

http-updated.txtin the user’s home directory.

- Read

Commands Used:

- Locate HTTP Services:

1 2 3

grep '^http[^x]' /etc/services > ~/http-services.txt grep '^ldap.[^a]' /etc/services > ~/lpic1-ldap.txt grep -v 'service$' ~/http-services.txt > ~/http-updated.txt

This summary provides an overview of the lab tasks, learning objectives, commands used, and the significance of practicing regular expressions in Linux system administration.

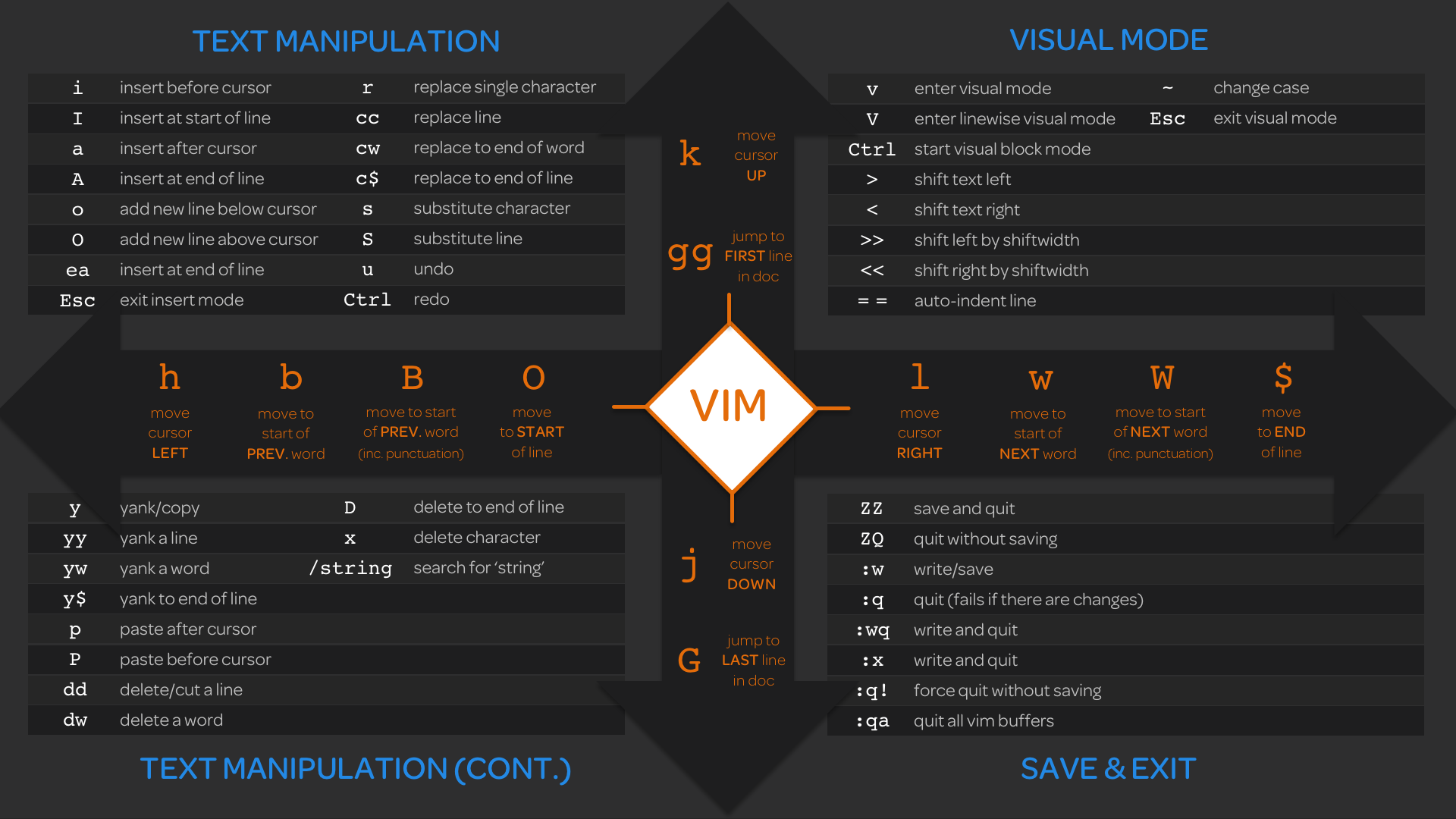

Lesson Summary: VI and VIM Text Editors

Overview:

- VI and VIM are powerful command-line text editors widely used in Unix-like operating systems.

- VIM is the modern successor to VI, offering more features and capabilities.

Getting Started with VIM:

- To start VIM, simply type

vimin the command line and press Enter. - VIM opens in command mode, allowing cursor movement and other commands.

- Enter insert mode by pressing

Ito start inserting text. - Exit insert mode by pressing

Esc. - Use

H,J,K, andLkeys for cursor movement (left, down, up, right).

Visual Mode:

- Visual mode allows selecting text for copying, cutting, or other operations.

- Enter visual mode by pressing

V, then navigate and select text. - Copy selected text by pressing

Y, then paste withP. - Undo actions with

U.

Saving and Quitting:

- Press